Previously published Mar 20. 2021

Throughout February, Myanmar has been facing a deadly coup which has caused extreme upheaval and unrest throughout the country. Aung San Suu Kyi won the first contested election in 2015 after campaigning and fighting for Myanmar’s democracy. She was jailed for 15 years due to on and off again house arrests before the election throughout 1989 and 2010 for organizing protests and rallies against the government. Recently, Aung San Suu Kyi’s role in the Rohingya Muslims’ atrocities has come to light. Myanmar has denied this minority from gaining citizenship due to the belief that Rohingya Muslims are illegal immigrants. Many have faced extreme persecution, with thousands killed and “700,000 [having] fled to Bangladesh following an army crackdown in 2017” (Cuddy, 2021). As a result, Aung San Suu Kyi was asked to appear before the International Criminal Court. She claimed that Myanmar had no role in the genocide of the Rohingya Muslims. This created the unrest’s origins through Myanmar, with a split between the persecuted minority and government. After Ms. San Suu Kyi was found to be conspiring alongside the military, democracy became a fragile topic.

The coup was centered around the elections that took place on November 8, 2020, where Ms. San Suu Kyi was elected as head of the National League for Democracy. The country’s powerful military refused to accept the election results since they believed in the presence of fraud. Discussion of a coup began to spread after the military tried to argue against the Supreme Court election and lost, resulting in threats of “taking action” and surrounding the Parliament with soldiers (Goldman, 2021). After taking control of the country, the commander in chief, Min Aung Hlaing, released statements discussing that he is for democracy and the people and will host a “free and fair election” to form a “true and disciplined democracy” (Cuddy, 2021). On February 16, Ms. San Suu Kyi and the president, Mr. Win Myint, were on a secret trial. Ms. San Suu Kyi faced charges of importing illegal walkie-talkies and violating the Natural Disaster Law by disobeying COVID-19 restrictions as she was seen interacting with crowd members. Mr. Win Myint was also charged with breaking the Natural Disaster Law, and Ms. San Suu Kyi was denied the right to legal representation. The trial is projected to take around a year and could result in Ms. San Suu Kyi detained in prison for six years and Mr. Win Myint for three.

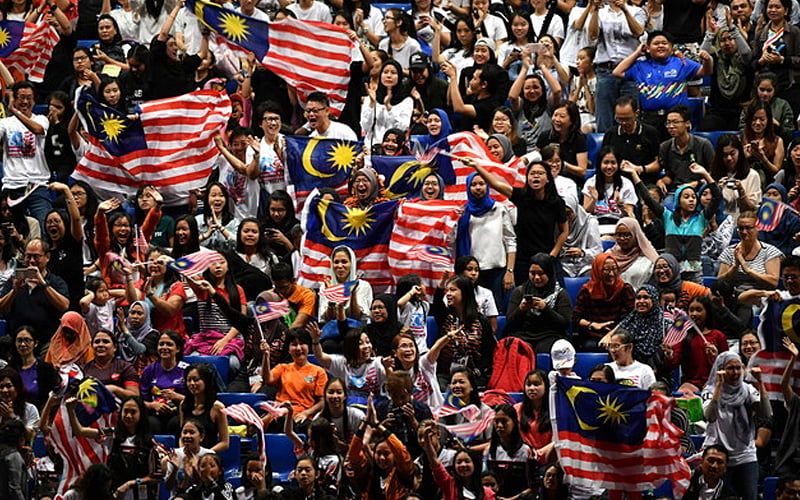

How have the people responded? The military coup resulted in many social media sites being blocked, cutting off the communication of Myanmar’s people from the rest of the world and preventing the civil disobedience movements from expanding. Furthermore, protests have erupted throughout the country. People have been demanding that Ms. San Suu Kyi be reinstated as she was their elected leader. Teachers, doctors, and some government workers have all taken part in joining these civil disobedience movements and refusing to work until their elected leader returns. The interim government has imposed a curfew, banned large gatherings, and threatened to take action against civil servants refusing to work (Aljazeera, 2021). These protests have taken a turn for violence, as many have resulted in police shooting rubber bullets into crowds and injuring many protestors.

Internationally, the coup is receiving a tremendous amount of backlash, with the UK and Canada placing sanctions onto the acting president in hopes of displaying their disapproval of the events taking place, and many countries such as the US, Japan, Australia, and India condemning the actions of the military and concurring that democracy must be restored (Aljazeera, 2021). Additionally, the EU has placed sanctions on Myanmar, and the UN Security Council demands the release of Ms. San Suu Kyi. Simultaneously, the UN Human Rights Council asks for a “refrain from violence against people protesting” (Aljazeera, 2021). Relations between the UN and Myanmar have grown strained with Kyaw Moe Tun, Myanmar’s ambassador to the UN, being fired by the military for asking the UN General Assembly for international aid. He was displayed to have “abused power and responsibilities of a permanent ambassador,” and Kyaw Moe Tun has now joined the protests (Regan and Gigova, 2021). The ambassador has gained recognition in the international field but struggles to help his citizens with the chaos and instability heightening. With the growing tensions in Myanmar, the countries democratic systems are now brought into question, which could potentially affect the fundamental ideals the government chooses to pursue in the future. While the country begins to rebuild, the government must consider which type of ideology, authoritarian or democratic, Myanmar will lean towards and focus on unifying the country under this government.

Sources

Aljazeera. “Timeline of events in Myanmar since February 1 coup.” Aljazeera.com, Al Jazeera Media Network, 23 February 2021, <https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2021/2/23/timeline-of-events-in-myanmar-since-february-1-coup>Accessed 1 March 2021.

Cuddy, Alice. “Myanmar coup: What is happening and why?” bbc.com, BBC, 1 March 2021, <https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-55902070> Accessed 1 March 2021.

Goldman, Russell. “Myanmar’s Protests, Explained.” NYTimes.com, The New York Times Company, 28 February 2021, <https://www.nytimes.com/article/myanmar-news-protests-coup.html> Accessed 1 March 2021.

Regan, Helen, and Radina Gigova. “Myanmar security forces open fire on peaceful protesters in deadliest day since coup.” CNN.com, Cable News Network, 1 March 2021, <https://www.cnn.com/2021/02/27/asia/myanmar-un-ambassador-fired-intl-hnk/index.html> Accessed 1 March 2021.

![Teacher [Milk] Tea: Part 2](https://bisvquill.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/Screen-Shot-2024-03-19-at-9.28.48-PM.png)