Imagine a night in Paris during the 1920s: you’re walking in the city of lights along the Champs-Elysées; the atmosphere around you is vibrant with the sounds of laughter and jazz music spilling out of clubs, cafes, and bars; a group of women with skirts and bobbed hair come walking toward you as they make their way to the nearest club, ready for a night filled with dance and music. Oh, the good old days, right? That’s what Gil from Woody Allen’s Midnight in Paris (2011) would think, too. In this romantic comedy, the protagonist, Gil, is captivated by the glamour of Paris in the 1920s, and constantly laments over the difficulties and blemishes of the modern day. The movie introduces us to “Golden Age Thinking,” or a false perception of the past, based on nostalgic sentiments and a longing for the simpler, more beautiful time. However, the film ultimately suggests that such thinking is misguided, as it encourages an unrealistic and unhealthy relationship with both the past and the present.

This way of thinking is not uncommon among people in today’s world. Take fashion, for example. In the past several years, vintage fashion has made its way back into the mainstream. One of the primary reasons for the comeback of vintage and retro fashion is the nostalgia that it brings. A similar phenomenon can be seen in the music industry, as evidence reveals that teenagers are increasingly listening to “old” music. A study conducted by New York University found that younger generations, including millennials, were more familiar with music from the 1960s and 1990s than with modern music. In both cases, people become attached to styles of the past, either because they evoke memories of simpler times or present a picture-perfect version of the past. While feelings of nostalgia can be valuable and personal, it would be a mistake to believe that another time period is preferable to the present simply because it seems ideal in our eyes. The problem with Golden Age Thinking is that it relies solely on a romanticized version of the past that we have artificially perfected for our tastes. Characterized by limited knowledge and false idealization, it constrains people to their own biases and leads them to overlook the nuances, flaws, and injustices of the past.

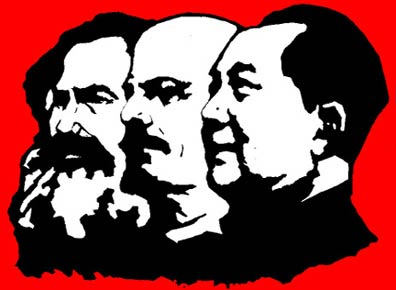

When people succumb to the fallacy of the Golden Age, they often simplify the past and ignore history’s complexities. At any point in history, there is both beauty and fault. One cannot speak of the music, art, and literature of Paris during the 1920s without acknowledging the economic hardship, social inequalities, and political instability that lay behind the surface-level beauty. Gil’s romanticization of 1920s Paris overlooks the harsh realities of that era. In focusing solely on the beauty of literary salons, jazz clubs, and great artists like Ernest Hemingway and F. Scott Fitzgerald, Gil creates an incomplete picture of the past. This selective memory, where only the highlights are remembered, is a natural part of nostalgia but ultimately prevents a clear understanding of history. In the same way, when people today romanticize previous decades, such as the 1950s or the 1980s, they often ignore the struggles and limitations of those times. Whether it’s political repression, social inequality, or technological constraints, every era has its share of problems. To think otherwise is to fall prey to a cognitive bias that sees the past through rose-tinted glasses. Every era may be viewed as someone’s “Golden Age,” but it is by no means perfect. This revelation comes when Gil, after being transported back in time to his idealized 1920s, meets characters from the 20s who themselves long for yet earlier periods, such as the Belle Epoque or the Renaissance. For those who lived during the 1920s, the past seemed more alluring, just as it does for Gil in his own time. This recursive desire for a different time shows that no era is without its flaws and challenges, and the human tendency to romanticize the past is a constant across generations. In the end, there is no one, true “Golden Age.”

At its core, Golden Age Thinking is a form of escapism, allowing people to avoid confronting their own problems or dissatisfaction with the present. Specifically in Midnight in Paris, Gil is an unsatisfied screenwriter, frustrated with his career and personal life. His longing for the past serves as a psychological escape from his own insecurities and challenges. By idealizing the 1920s, he avoids facing the difficulties of his relationships and career choices in the present. The past, in his mind, becomes a refuge from the complexities of the now. Because of this, Golden Age Thinking can lead people to undervalue or resent the present moment. When people are consumed by nostalgia, they may miss the opportunity to fully engage with the present and the benefits it has to offer. Escapism, while soothing in the short term, keeps people from adapting to new realities and finding contentment in the present.

Finally, Golden Age thinking overlooks the importance of progress and change. The world is constantly evolving, and while not all change is positive, it is through progress that society advances. By idealizing the past, individuals risk rejecting or resisting necessary changes that could improve the present and future. Gil’s journey in Midnight in Paris ultimately leads him to understand that the nostalgia he once embraced was preventing him from growing as a person and finding his own path forward. In the end, he must come back to the present and pursue his career with a realistic mindset.

Golden Age thinking, as exemplified by Gil in Midnight in Paris, is a seductive but ultimately flawed mindset. By idealizing the past, individuals risk distorting reality, avoiding personal growth, and undervaluing the present. Every era has its own challenges, and longing for a different time prevents people from fully engaging with the opportunities available to them today. Rather than succumbing to the allure of nostalgia, it is far more productive to appreciate the present, embrace change, and work toward building a future that incorporates the best aspects of both past and present. So, yes, you can certainly continue appreciating Monet’s art or listening to the Beatles, but remember that each time period offers its own value, so don’t let a romanticized version of the past blind you from the opportunities and possibilities available in the present.

Sources

Carlson, Ben. “Golden Age Thinking.” A Wealth of Common Sense, 31 December 2020, https://awealthofcommonsense.com/2020/12/golden-age-thinking/. Accessed 17 October 2024.

Devitt, James. “Young people know more old music than you’d think.” Futurity, 7 February 2019, https://www.futurity.org/music-young-people-1975982/. Accessed 17 October 2024.

“Exploring the Magic and Realities of 1920s Paris.” Medium, 2 May 2023, https://medium.com/@woodyallenfilms/exploring-the-magic-and-realities-of-1920s-paris-b11c4c8dea6b. Accessed 18 October 2024.

“The Fallacy of the Golden Age: Leave the Past in the Past.” Medium, 5 September 2023, https://medium.com/@thinknewsnow/the-fallacy-of-the-golden-age-leave-the-past-in-the-past-149321bbf13d. Accessed 17 October 2024.

Holmes, Leslie. “The Return of Vintage: Why Old School Styles are New Again.” Medium, 28 December 2023, https://medium.com/@leslie.holmes.writing/the-return-of-vintage-why-old-school-styles-are-new-again-a5615ad15e1d#:~:text=Nostalgia%20and%20Timeless%20Appeal,’%20or%20grandparents’%20fashion%20choices. Accessed 17 October 2024.

Lieberman, Charlotte. “Why We Romanticize the Past.” The New York Times, 2 April 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/04/02/smarter-living/why-we-romanticize-the-past.html. Accessed 17 October 2024.

Matthews, Caroline. “Golden Age Thinking – is it fallacy, or a useful coping mechanism?” Health Magazine, January 2023, https://www.health-magazine.co.uk/post/golden-age-thinking-is-it-fallacy-or-a-useful-coping-mechanism. Accessed 17 October 2024.

Warwick Business School. “Why we think life was better in the ‘good old days’ | News.” Warwick Business School, 13 January 2015, https://www.wbs.ac.uk/news/why-we-think-life-was-better-in-the-good-old-days/. Accessed 17 October 2024.

![Teacher [Milk] Tea: Part 2](https://bisvquill.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/Screen-Shot-2024-03-19-at-9.28.48-PM.png)