Growing up as a Chinese-American, I was surrounded by stories of the exploits of great Chinese people, especially the country’s generals. As I learned more about the notable battles of Chinese history, I became convinced that the military strategies employed in those battles were the most sophisticated in all of human history. Even after learning of the battles from other parts of the globe, I maintain this very arrogant and presumptuous opinion. Today, I seek to convince you of the same. So without further ado, here are the most “bigbrain” moments in Chinese military history.

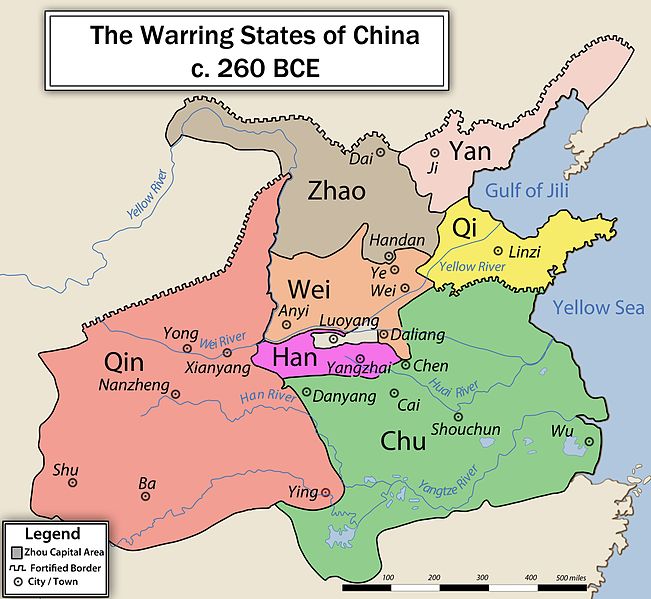

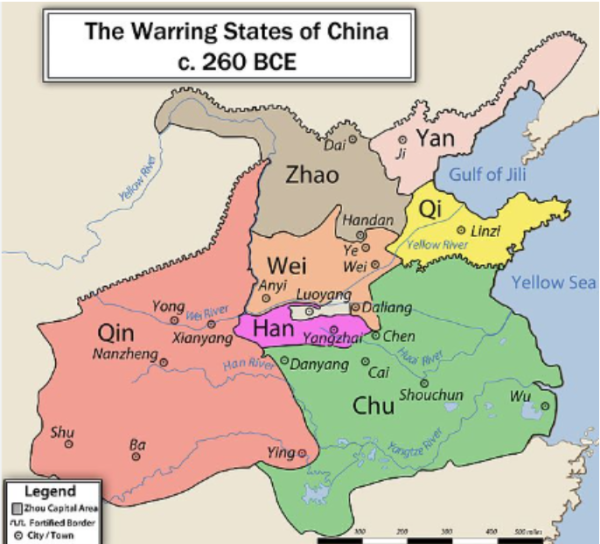

Battle of Changping (长平之战) (260 BC): Allow me to set the scene. Though the Kingdom of Qin was the preeminent power of China, they were still a decisive victory away from defeating the other six nations that controlled the country. Now, the state’s elite troops, totaling 400,000 men, are stationed on the Western side of the Dan River, at its Northeastern border, facing a similarly-sized army gathered by the King of Zhao. The victor of this battle would certainly become the first in 500 years to unify China.

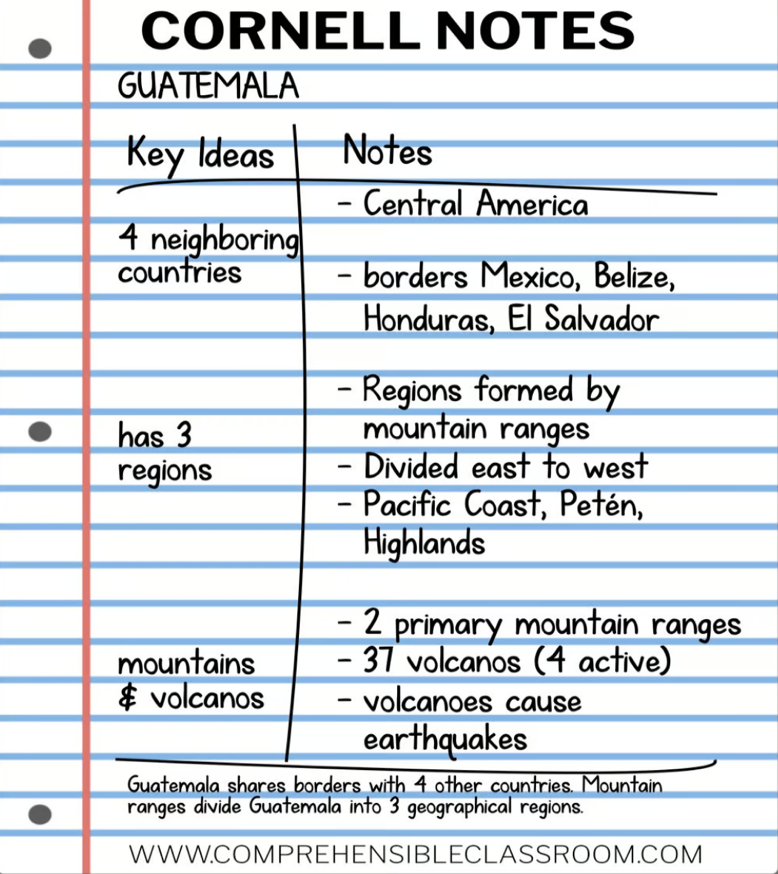

(Here’s a Map of China during this period)

For two years, neither army made a move. The Qin were led by the experienced Bai Qi (白起) and the Zhao by the similarly veteran Lian Po (廉颇). But in 260 BC, the King of Zhao made the inexplicable decision to replace him with Zhao Kuo (赵括), who, by the way, had literally never led an army in battle before (as you can probably tell, this isn’t going to end well).

Immediately after taking command, the impulsive Zhao Kuo noticed the weakness of the Qin army’s left flank, and sent his entire army across the river to destroy it. He would not realize his fatal mistake until it was too late, as this was exactly what Bai Qi had wanted.

In a move that would foreshadow the great Napoleonic battle of Austerlitz, Bai Qi’s left flank fell back, luring its pursuers into the Dan Valley, a few miles west of the river. Then, the Qin troops turned and blockaded themselves into pre-prepared fortified positions. Just as the Zhao troops were preparing to dislodge these defenders, from the Northeast and Southeast, the sound of drums echoed through the air as the remaining contingents of Bai Qi’s army closed in, cutting off all trails leading in and out of the valley. The Zhao army was now trapped, without food or water.

For the first time in Chinese, and possibly even world history, an army had successfully encircled another of similar size.

The Qin army killed Zhao Kuo in battle and captured 200,000 Zhao troops, all of whom Bai Qi ordered to be buried alive. The Battle of Changping remained the deadliest battle in world history until the 1258 Siege of Baghdad (nearly 1500 years later!), and it paved the way for Qin Shihuang’s eventual reunification of China in 221 BC.

Battle of Jingxing (井陉之战) 205 BC: For thousands of years, one of the inviolable rules of war was this: never place your army in front of a river, lest it be trapped in a rout. It was treated like an Iron Law, as ‘never dig straight down’ is in Minecraft. But as this battle shows, even Iron Laws can, from time to time, be broken.

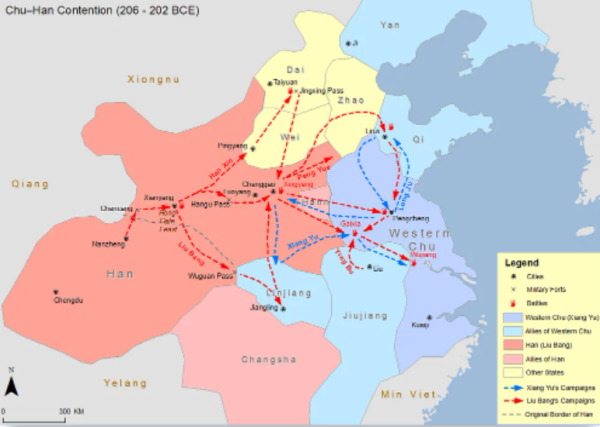

Only four years after the death of Qin Shihuangdi, the Qin dynasty collapsed. China fell into anarchy once more. Here is a map!

As you can probably tell from the map, by 205 BC the Han kingdom was starting to look like the dominant power in the country. Still, it had to bulldoze some formidable enemies until the goal of reunification could be achieved.

At this time, Han Xin (韩信), the top Han general, was tasked with invading the Northern Kingdom of Zhao (a different one from before). However, in the middle of his campaign, much of his army was redeployed Southwards to defend against an external threat, thus leaving him with only 30,000 troops against an enemy force of nearly 200,000. Any other general would have chosen to retreat, to establish a defensive line and seek another opportunity to invade. But not Han Xin.

The day of the battle had arrived. At the break of dawn, Han Xin gathered his troops and provided each soldier with only enough food and water to last till dusk. Then, he arrayed his battle line in front of the Tao River (洮水). The Zhao army quickly trapped them between their battle lines and the river. Then, as the sun rose into the heavens, Han Xin turned to his men and cried out something to the effect of, “You either fight your way out or drown in the river behind you. There is no other way!”

Hearing these words, the Han army became ferocious warriors. In a battle that shook the Earth, 200,000 Zhao troops were completely decimated by the significantly smaller yet wildly tenacious Han army.

To my knowledge, no other general in human history will ever again have the guts to trap his own army to encourage them to fight harder. This battle even inspired a Chinese saying, familiar to many Chinese students: 背水一战 (to fight with one’s back to the river).

Battle of Red Cliffs (赤壁之战) 208 AD: This story is a complex one, and one which fans of the novel Romance of the Three Kingdoms (三国演义) will be very familiar with. I will divide up the events of the battle into three key parts. But before I can do that, I have to set the scene (as always).

After 400 years of prosperity, the Han Dynasty is nearing its end, and its emperors have been reduced to ceremonial figureheads. Three warlords—Cao Cao (曹操) in the North, Liu Bei (刘备) in the Southeast, and Sun Quan (孙权) in the Southwest—wielded hegemony over the entire nation. Cao Cao, recognizing his status as the most powerful and not wanting to allow time for his Southern counterparts to strengthen their forces, gathered 200,000 men into a Grand Fleet and sailed down the Yangtze River.

(unfortunately, there are no good maps of this period that I can use without BISV getting sued, but if you search up ‘China Three Kingdoms Period Map,’ you should be able to find it)

Sun Quan and Liu Bei decided to form a coalition to counter the Northern threat, but their combined force was only 50,000 strong. (If you know the trajectory of this article, you can probably already guess who’s going to win this battle, but no spoilers!) They knew that their only hope was to defeat the Cao army on the water, where the Northern forces could not as easily exploit their numerical advantage. Thus, they hatched an ingenious plot.

Step 1: Eliminate their Commanders: The coalition knew that the Northern armies were inexperienced in naval combat, but for now, their morale was being held up by the deft command of Admirals Cai Mao (蔡瑁) and Zhang Yun (张允). To win the battle, they had to be eliminated first.

Overconfident in his manpower superiority, Cao Cao sent an envoy to the coalition camp, urging them to surrender. The coalition treated the envoy very well, and even “accidentally left” some “classified” letters out in the open, which he promptly stole.

Fleeing back to camp by night, the envoy presented the letters to Cao Cao. The letters appeared to reveal Cai Mao and Zhang Yun’s plan to abandon Cao Cao and offer their services to the coalition side. In a fit of rage, Cao Cao ordered both generals executed. It wasn’t until their heads were brought back into camp that he realized the letters were forged.

Step 2: Tie Their Ships Together: Now, the coalition began the second part of their plan. Despite the death of the Northern army’s adept generals, defeating the numerically superior Cao army in a head-to-head confrontation would still be an insurmountable task. Thus, the coalition decided to implement a new strategy–“flame warfare.”

But simply lighting the enemy ships on fire wouldn’t be enough. If one ship went up in flames, the others would simply flee. Then, the whole plot would fall through. There was also no way to ignite every ship at once. What would the coalition do?

This was when Pang Tong (庞统), one of Sun Quan’s advisors, cracked a sneaky plot. He went to Cao Cao’s camp, pretending to surrender to his side. At the time, the Northern armies were widely incapacitated by sea sickness. Leveraging this opportunity, Pang Tong advised Cao Cao to stabilize his ships by tying them all together with metal chains.

Soon, Cao’s armies stopped barfing all over the deck. Elated by this “success,” Cao Cao awarded Pang Tong a hefty amount of silver and allowed him to return home.

Step Three: Get Close: All the pieces were in place, but the coalition was still missing a plausible reason to get close enough to Cao’s ships to set them aflame. Just then, Huang Gai, (黄盖), a fearless general, conceived a plan that would only be shared with the commander of the coalition forces, Admiral Zhou Yu (周瑜).

At a meeting of the coalition’s generals, Huang Gai stood up before his commanders and suggested the coalition surrender to the superior Cao forces. “Infuriated” by this treasonous suggestion, Zhou Yu ordered for him to be beaten within an inch of his life. For many months, the general was bedridden.

Around this time, a letter was sent to the Cao camp by none other than Huang Gai, promising that he would surrender with a portion of the coalition fleet to his side. Cao Cao, having heard of his cruel beating, did not doubt the veracity of his capitulation.

Huang Gai had used his blood and bones to buy the trust of Cao Cao’s suspicious mind.

Step 4: Fire!: On a cold winter day, as the wind blew northward, directly in the face of the Cao army, Huang Gai set out with dozens of light ships filled with flammable reeds. As he approached, Cao Cao realized that something was amiss. The ships were moving too slowly to be empty! But it was too late. The ships were set alight as they collided with the forward detachments of the Northern fleet. The heavy northern wind carried the flames further and further in that direction, crippling the Cao fleet. Not a single ship could flee, thanks to the metal chains suggested by Pang Tong. Within minutes, the entire Northern army was decimated.

Cao Cao was forced to pull back and organize troops to defend his own territory, and he would never be able to invade the South again. The stalemate of the Three Kingdoms was thus solidified.

Are you now convinced of the superiority of Chinese military history? If you’re not, can you come up with examples of even more genius moments? If so, please let me know, because I’m genuinely curious about what stories there are out there.

Work Cited

Most of this information comes from the history podcasts of Chinese historian Yuan Tengfei (袁腾飞). By the way, if any Chinese teachers are reading this, you should definitely recommend (read: force) your students to watch his history videos on YouTube. I personally love him.

![Teacher [Milk] Tea: Part 2](https://bisvquill.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/Screen-Shot-2024-03-19-at-9.28.48-PM.png)