The Early Years

Chess began in the Indian Gupta Empire as a miniaturized version of war. Its pieces, including cavalry, elephants, and foot soldiers, represented the key components of the army. Generals would be expected to be proficient in the game, as it was seen as an exercise for commanding an actual army. The game soon spread to the rest of the continent, advancing to Persia and Asia via merchants. In each nation, the rules of the game changed to suit the unique culture and customs of that empire.

For example, Chinese chess has a unique aspect known as “the Chu River” between the two sides of the board. This is not present in other versions of this game.

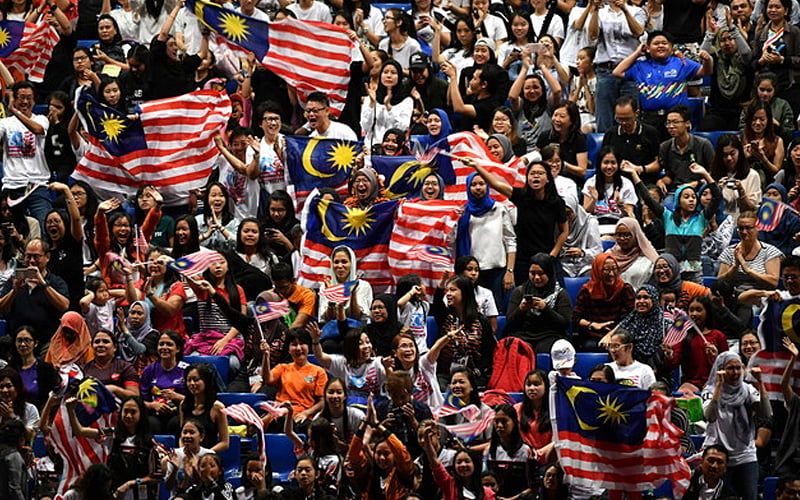

This popular pastime was not constrained to Asia’s borders. By 1200 CE, the game spread to Europe, beginning with its eastern fringes and gradually spreading west. Even the Vikings played chess!

Replicas of Viking chess pieces. They look so bored!

From the 1200s to the 1700s, chess gradually developed into its modern form. Dominating Western European upper-class establishments, chess became a symbol of sophistication, education, and class.

For the remainder of this article, I will reference famous games throughout chess history. I will be using chess notation and images of the board. The game of chess is not overly complex, but I simply won’t have time to explain all of its rules. Nevertheless, even if you don’t understand how to play the game, I hope my discussion of its history will still be fascinating enough to motivate you to read on!

The Romantic Age

The seventeenth century was an era of discovery for the game of chess. Before computer algorithms could calculate the mathematically perfect continuation of any game, players experimented with aggressive, elegant, and often stupid moves, hoping to uncover secrets yet to be discovered. This was an era where past games were not yet preserved, so every move you made could be totally new and bring the entire chess world down a path never seen before. To the players of the seventeenth, eighteenth, and nineteenth centuries, the game of chess was as mysterious as the Jungles of Burma, as Romantic as the music of the age, and as bombastic as the cannons that were scattered across European battlefields.

Gioachino Greco

One of the earliest masters of the Romantic era was Gioachino Greco, an Italian player and author who wrote and sold books on chess for nobles. Many of the most elegant checkmates in the game were invented by this player. At a time when most players viewed the capturing of enemy pieces as the best path toward victory, Greco’s eyes were always honed toward one and only one thing: the enemy king.

Often, Greco would allow his enemies to capture an absurd number of his pieces, giving them the brief illusion of victory, before thundering back with a devastating attack to annihilate the enemy king (for the two of you who don’t know, in chess, if the king is under attack and cannot escape, it is deemed “checkmated” and thus the game is over).

Here’s my favorite example, courtesy of Chess.com!

But before I continue, here is a quick rundown of how chess notation works:

From left to right is a row, and starting from the white side of the board, we get rows 1, 2, 3, etc. Up to down is the file, which is designated a, b, c, etc. Each square, therefore, has its own file and row.

Kings are denoted K, bishops B, knights N, rooks R, and queens Q. Pawns are not denoted with anything. For example, g5 means pawn to g5, but Ng5 means knight to g5.

“x” denotes a capture; if it is a pawn capturing something, you note which file the pawn started out on and which it moved to. For example, exf5 means a pawn from the “e” file captured a piece on f5. Rxf5 means a rook has captured a piece on f5.

“+” denotes a check, when the opposing king is under attack.

“#” denotes checkmate, the end of the game.

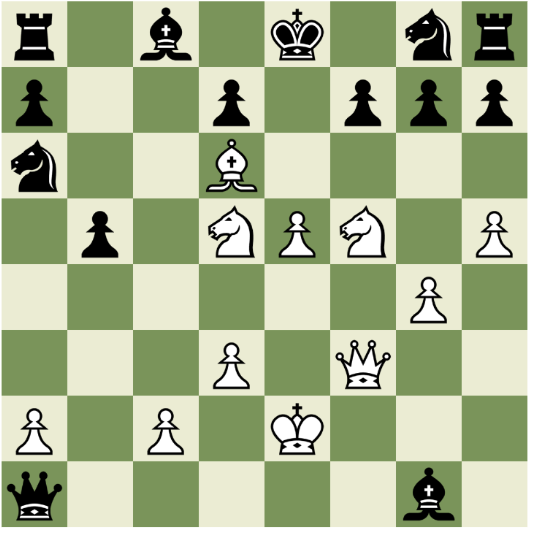

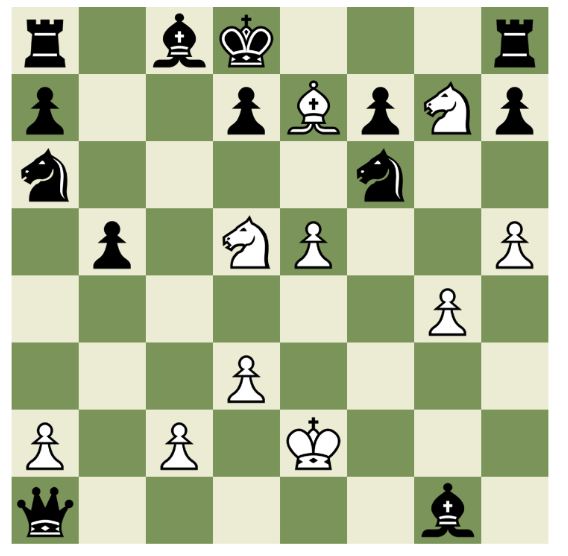

Greco (White) vs. Anonymous (Black), 1623 Courtesy of Chessgames.com

It’s only the opening, and all seems calm. Greco will not let that last.

Black tries to break open the center with the honestly questionable f5. Greco responds exf5.

Black, thinking he has tricked his opponent, seizes a pawn with Bxg2, trapping Greco’s rook in the corner. What is Greco to do now?

Greco, unfazed, lashes out with Qh5+! Black responds with the desperate g6, which is immediately captured (fxg6). Black tries one final defensive maneuver with Nf6, attacking the Queen and hoping to force it into retreat. But Greco does not oblige. gxh7+!

Black captures the queen with Nxh5. I’d like to believe that even in this last moment, he did not realize that brutal mate was about to be delivered upon him.

Greco ends the game with Bg6…checkmate.

Adolf Anderssen’s Immortal Game

Greco was indeed a great player, but the game during his time had not yet been internationalized. Therefore, there was no way to determine his strength compared to other top players around the world. But by the nineteenth century, that comparison became possible. A combination of the international appeal of chess and the continued romanticization of the game made the precious early years of that century the most wonderful years in the game’s history.

There are two players who are undisputedly the greatest of the era. One was German master Adolf Anderssen; the other was American genius Paul Morphy. Early on, Anderssen was widely considered the best player, boasting a record of near-impregnable play. His most notable game, aptly named the Immortal Game, is still studied to this day.

Buckle up, cause this next analysis will not be so liberal with pictures!

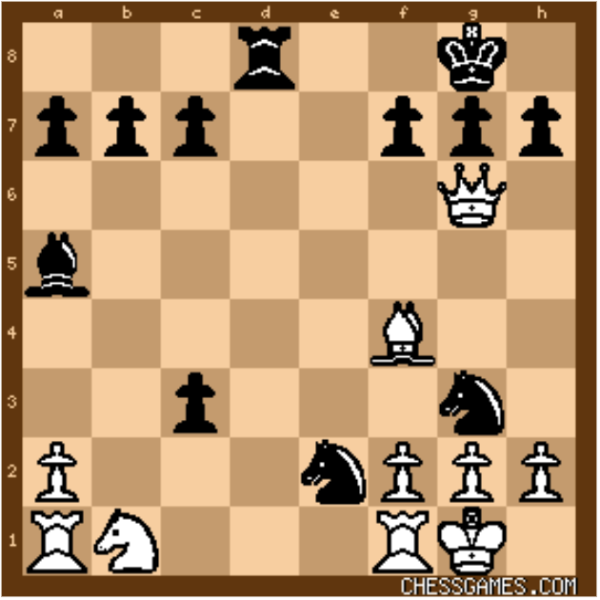

(White) Adolf Anderssen vs. Lionel Kieseritzky (Black) (1851) Courtesy of Chess.com

At first glance, this position on move 17 is one of absolute chaos. Anderssen has already sacrificed a bishop for the attack, and now both his rooks are under the deadly glare of Kieseritzky’s pieces. What shall Anderssen do? Defend? It’s the Romantic Era! Absolutely not!

Anderssen, rather than defending his own king, goes for the absolutely bonkers Bd6, cutting off Black’s dark-squared bishop from defending his own king. Black responds by capturing white’s rook on g1 with his bishop. Anderssen responds e5, a seemingly innocuous move. Yet what it does is insidious, and would prove pivotal.

The move e5 interfered with the Queen’s ability to defend the pawn on g7, and Kieseritzky likely realized this as well. After snatching the other rook with Qxa1+, forcing Anderssen’s king to e2, Kieseritzky plays the only defense available to him: Na6.

Black’s idea is clear. After White plays Nxg7, forcing black’s king to d8, there would be no Bc7 checkmate. When Anderssen indeed captured the pawn on g7, Kieseritzky slid his king to the side, believing he was safe…

In this position, down two rooks and a bishop, facing a seemingly unwinnable position, Anderssen doles out the fatal blow. Qf6+!! This move simply hands Black the queen! Yet after Nxf6, rather than recapturing the knight with his pawn, Anderssen ends the game with the magnificent Be7#…checkmate.

The epitome of beauty.

Paul Morphy

If the Romantic Age of chess were imprinted into the musical age of the same name, then Morphy would have been its Mozart. It is said that past the age of 13, Morphy never lost a game, not even against Anderssen. When he reached his prime, he superseded Anderssen in strength and became the undisputed best in the chess world. Of course, that’s not to say that he won every game, since a majority of his and other masters’ games ended in draws (ties). But this record is impressive nonetheless, and would never be achieved again.

Morphy was a master of positional and tactical chess. To select a game with incredible craft would be like dipping my hand in a lake searching for droplets of water. There are simply too many examples. Therefore, I will only present my favorite, a short yet decisive ending.

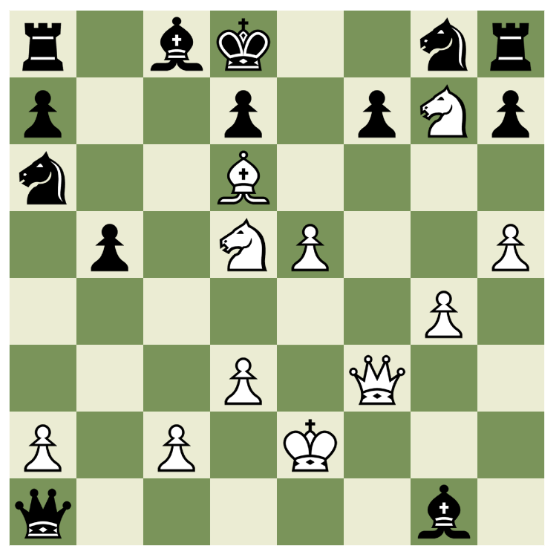

(White) Napoleon Marache vs Paul Morphy (Black) (1857) Courtesy of Chessgames.com

In this position, Morphy with the Black pieces is clearly ahead in development, but to the untrained eye, there seems no way to win a quick victory in this position. White has just played Qe4, centralizing that piece.

Here, on move 19, Morphy plays the shocking Ng3!

The move seems utterly insane! This knight can now be captured by three different pieces! Yet none can do so, because the queen on e4 is hanging, undefended, and being threatened by Morphy’s queen on g6. “No problem,” Marache thought to himself, calmly capturing it with Qxg6. “Once Morphy recaptures the queen, I will capture his knight!”

But Morphy did not recapture. Instead, he dropped the bombshell Nde2#!

I would like to believe that Marache, not seeing this coming, fell out of his chair, or otherwise leaped forth in shock. The position is chaos, yet in the chaos, Morphy discovers this beautiful checkmate. True connoisseurs of this delicate game would join me in recognizing this match’s astounding charm.

In 1830, bored by this game he seemingly could not lose, Morphy quit chess to become a lawyer, a job which he was, unfortunately, not very good at. But his legacy was one of tactical brilliance, and his games were an embodiment of the Romantic Era. Thereafter, it seemed that Morphy’s style was bound to live on through other, lesser players.

And then Wilhelm Steinitz appeared in the chess world…

TO BE CONTINUED…

File:British Museum – Room 40 Lewis Chess Pieces (20416690091).jpg. (n.d.). Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Beserker,_Lewis_Chessmen,_British_Museum.jpg

![Teacher [Milk] Tea: Part 2](https://bisvquill.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/Screen-Shot-2024-03-19-at-9.28.48-PM.png)