(This article largely contains research and writing done by other peers: Ava C. (2), Alaina M. (3), and Wenhan (Aubrey) S (4))

Nine hours of school, nine hours of following rules, nine hours of studying molecules, and finally it’s time to hit the hay. Within the walls of the University of Chicago, I found myself falling into deep slumbers as soon as my head hit the pillow after my entire day went into, ironically enough, studying sleep. This summer, a prestigious college gave me the opportunity to research the extent to which melatonin deficiency relates to Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). Teaming up with a few of my lab mates, we studied the theories surrounding the correlation of these two topics and proposed a solution for future scientists to look into. This article will explore a diverse range of scientific literature, both primary and secondary, and each piece of literature will talk about different ways that melatonin and autism are correlated (1).

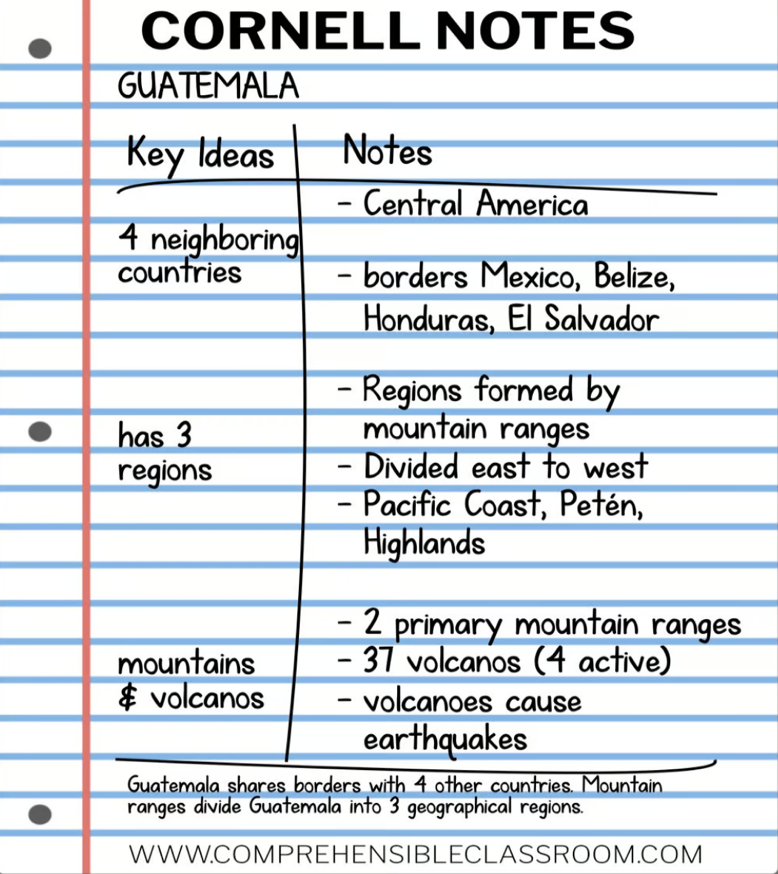

But before we get into the nitty-gritty, pulling our brains out, sciencey stuff, what is ASD? Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is a neurodevelopmental condition that results in a neurological difference in the brain. ASD affects the way individuals perceive and interact with the world, thus altering their day-to-day experience to be different from those who are neurotypical. Key characteristics of individuals with ASD include sensory sensitivities to visual, auditory, and tactile surroundings; engaging in repetitive behaviors, also known as stimming; hindrance of social communication abilities; and challenges in expressing and understanding the emotions of themselves and others. One common characteristic of autism relevant to this specific research project is the low levels of melatonin among individuals with ASD (2).

Melatonin is a hormone produced by the body that regulates sleep-wake cycles in a circadian (every 24 hours) rhythm. It is a necessary component in causing sleep, and a lack of light stimulates the production of melatonin. Low levels of melatonin can be seen in individuals who have trouble sleeping and are often treated with melatonin supplements. Melatonin deficiency, however, is related to severe depletion of melatonin within the brain and, thus, can be correlated with many neurological disorders (1).

It has been found from various studies that low levels of melatonin and ASD are correlated to an extent, with melatonin’s role in not only managing the circadian rhythm but also in anti-inflammation and regulation of synaptic plasticity. It plays a critical role in regulating the body’s internal clock, helping to synchronize sleep patterns in coordination with light signals (3). A study done by Daniel E Rossignol and Richard E Frye shows that a specific gene that was found to be associated with this issue was the ASMT gene polymorphisms. The ASMT gene is a segment of DNA that encodes a protein, specifically an enzyme, which plays a crucial role in the synthesis of melatonin. Some polymorphisms and abnormalities mentioned in this study were single-nucleotide polymorphisms, gene duplications, and stop mutations, and these have been suggested to contribute to low levels of melatonin in children with ASD. While some of these polymorphisms were also found in individuals without a diagnosis of autism, the researchers concluded that it was more common among individuals with ASD. These differences in the ASMT gene, according to researchers, were correlated with lower secretion of melatonin. The decreased secretion is caused by limited enzyme activity of a protein that is coded by the ASMT gene (2, 1).

The pineal gland—a prominent part of the brain that plays a role in melatonin production—may have a large influence on ASD development. The pineal gland is located in the center of the brain and positioned on top of the third ventricle, which allows it to secrete hormones and chemicals into the CSF (cerebrospinal fluid) and blood. Individuals with autism display signs of sleep deficiency and low melatonin levels.

Moreover, abnormal neural plasticity was speculated to be linked to autism development. While there is not one specific cause identified for ASD, melatonin plays a critical role in regulating circadian rhythms, the sleeping and waking cycle, and early embryo development with neuroprotective effects on the fetal brain. Genetic mutations in melatonin-associated enzymes including AANAT and ASMT have been observed in multiple cases of ASD. The specifics of these enzymes don’t have to be clearly understood—the central idea is that enzymes associated with melatonin have also been found to be correlated with ASD (2, 1).

A study done by Borsani et al. explored the impact of melatonin on autism spectrum disorders using BTBR mice. The objective was to investigate the potential therapeutic effects of melatonin on a mouse model of autism and to understand its mechanisms. In the experiment, male transgenic mice, starting at 6 weeks old, received daily doses of melatonin (10 mg/kg) or a control solution for 8 weeks. Researchers then examined biochemical markers in the prefrontal cortex and studied the behavioral assessments to evaluate the effects of melatonin administration. Although the behavioral results were not statistically significant between the two groups, there were encouraging biochemical outcomes. Previous studies have indicated that ASD inhibits the functionality of GABA, increases blood glutamate levels (Rojas, 2014), and heightens oxidative stress and inflammation (Rossignol & Frye, 2014). These factors can coalesce to disrupt synaptic connections and cause excitotoxicity. In this study, melatonin enhanced antioxidant activity, stabilized the balance between GABAergic and glutamatergic systems, and supported synaptic remodeling in BTBR mice models. Specifically, melatonin decreased glutamatergic receptors while improving GABAergic transmission, and its antioxidant effects led to reduced inflammation. Thus, melatonin may offer therapeutic benefits for ASD by improving biochemical pathways.

It is known that melatonin is a naturally occurring hormone in the human body that is specifically connected with our sleeping quality. In a study done by Tordjman et al., 49 children and adolescents with ASD’s levels of melatonin are measured. It turns out that the nocturnal production of melatonin is significantly reduced in ASD patients, and there is a reported mutation in the gene for melatonin. Therefore, the enzymes involved in the production of melatonin have changed, but, the underlying relationship of why autism is linked with the reduction of melatonin remains unknown (4).

Due to the time constraints and limitations on experimental technology, we weren’t able to test our hypothesis and discover the true correlation between melatonin deficiency and ASD, if any. However, we were able to develop a potential method of experimentation that future scientists may look into, should they continue to research our topic (1). To begin, they would have to understand the gap within our field of research—whether the damage associated with the pathways of melatonin synthesis is a cause or a consequence of ASD. The significance of filling this gap could lead to greater advancement in research and therapeutic strategies that could be used to help remedy some of the ASD symptoms. Further scientific understanding of the brain could also lead to greater compassion and understanding of those with autism, possibly reducing stigmatization of it (2). A potential strategy we could use to fill this gap is doing a gene knockout of ASMT within mice in order to reduce or inhibit melatonin production. We would then see if this causes changes in neurological phenotypes or behaviors that correspond to ASD. To ensure that the observations we made are due to the changes we induce, we can re-input melatonin in the mice’s brains to see if that reverses the phenotypes or not (1, 2).

(1) synaptic plasticity: the ability of synapses to change the strength of their synaptic connections

(2) a gene that has more than one allele at a specific location in a population

(3) third ventricle: a narrow, funnel-shaped cavity in the brain that’s responsible for producing, secreting, and transporting cerebrospinal fluid (CSF)

(4) CSF: cerebrospinal fluid is a clear, watery liquid that protects and nourishes the brain and spinal cord

(5) circadian rhythm: the natural, 24-hour cycles of physical, mental, and behavioral changes that occur in the body.

(6) AANAT: an enzyme that plays a role in the rhythmic production of melatonin, adjusting its levels between day and night by modifying serotonin.

(7) ASMT: an enzyme primarily found in the pineal gland that plays a crucial role in the final step of melatonin synthesis, converting N-acetylserotonin into melatonin, a hormone vital for regulating sleep cycles

(8) BTBR: a strain is used in studies of autism due to its ability to display several symptoms of autism including reduced social interactions, impaired play, and unusual vocalizations

(9) GABA: a naturally occurring amino acid and neurotransmitter that slows down the brain by blocking signals in the central nervous system

(10) glutamate: an amino acid and neurotransmitter that plays a key role in brain function (learning, memory, and mood regulation)

Sources:

Wright KP Jr, Badia P, Myers BL, et al. Caffeine and light effects on nighttime melatonin and temperature levels in sleep-deprived humans. Brain Res. 1997;747(1):78-84.

Wright KP Jr, Myers BL, Plenzler SC, et al. Acute effects of bright light and caffeine on nighttime melatonin and temperature levels in women taking and not taking oral contraceptives. Brain Res 2000;873:310-7.

Mays, JC.; Kelly, MC.; Coon, SL.; Holtzclaw, L.; Rath, MF.; Kelley, MW.; Klein, DC. Single-cell RNA sequencing of the mammalian pineal gland identifies two pinealocyte subtypes and cell type-specific daily patterns of gene expression. Public Library of Science. 2018;13(10):e0205883–e0205883.

Lord C, Elsabbagh M, Baird G, Veenstra-Vanderweele J. Autism spectrum disorder. Lancet. 2018 Aug 11;392(10146):508-520. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31129-2. Epub 2018 Aug 2. PMID: 30078460; PMCID: PMC7398158.

Rossignol, D. A., & Frye, R. E. Evidence linking oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and inflammation in the brain of individuals with autism. Frontiers in Physiology. 2014 April 22; 5, 150.

Rojas, D. C. The role of glutamate and its receptors in autism and the use of glutamate receptor antagonists in treatment. Journal of Neural Transmission. 2015 Aug 1; 121(8), 891–905.

Borsani, E., Bonomini, F., Bonini, S. A., Premoli, M., Maccarinelli, G., Giugno, L., Mastinu, A., Aria, F., Memo, M., & Rezzani, R. (2022). Role of melatonin in autism spectrum disorders in a male murine transgenic model: Study in the prefrontal cortex. Journal of Neuroscience Research, 100(3), 780–797. https://doi.org/10.1002/jnr.24997

Tordjman S, Anderson GM, Pichard N, Charbuy H, Touitou Y. Nocturnal excretion of 6-sulphatoxymelatonin in children and adolescents with autistic disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2005 Jan 15;57(2):134-8. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.11.003. PMID: 15652871.

![Teacher [Milk] Tea: Part 2](https://bisvquill.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/Screen-Shot-2024-03-19-at-9.28.48-PM.png)