Previously published Mar 20. 2021

“While the rest of India has modernized, Indian agriculture has stagnated,” writes reporter Lauren Frayer on NPR. Like many developing nations, India is a country that relies heavily on agriculture for self-sustenance and its primary food source. However, this sector’s workers have been overlooked for a large part of history, and while reforms have been made, the process has been slow and much uncertainty remains over whether more harm or good has been done.

In the 1960s, a system of subsidies was implemented to aid farmers with their crop yields. This was one of the most monumental steps taken by the government to benefit farmers as part of an overarching movement known as the “Green Revolution.” However, since then, many farmers have remained impoverished, and with around 800 million Indians working in agriculture, this issue is becoming more blatant in society (Frayer, 2021). India has seen numerous protests, a rise in suicide rates among farmers, and growing poverty rates. As a result, Prime Minister Narendra Modi implemented three laws: The Farmers Agreement on Price Assurance and Farm Services Act, The Farmers’ Produce Trade & Commerce Act, and The Essential Commodities Act to combat this issue. These laws essentially promote free trade in the agricultural sector, looking to encourage business outside government control.

The dispute over these laws rests because many Indians do not believe less government control is the solution. With the general success seen with the Green Revolution, the farmers are asking for an increase in government aid. One of the portions already provided is known as the Minimum Support Prices, a list of twenty-two staples that fall under price guarantees by the government. However, many of the staples on the list are not utilized by most farmers, and vital goods such as pepper are excluded, thus resulting in many not receiving the aid they need to uphold their businesses. Along with this, there is a wide disparity in the provided assistance based on geographical location. Many states are not receiving the same subsidies as others, as described by Ambadas Sanap, who discusses how he lacks the electrical subsidies that other farmers receive, and another farmer, Chetan Lodha, explains how there is no access to proper water supplies at his farm (Frayer, 2021). With these essential utilities not being widely accessible, many farmers are struggling to keep their lives afloat. Another significant issue with Modi’s reforms is regarding the Agricultural Produce Marketing Committee (APMC). This is a large arena where farmers can buy, sell, and exchange goods at government-set prices. Lodha explains how with this system put into place, many farmers have not been exposed to basic marketing techniques and have never entirely taken on selling their goods.

With a free market, Modi would essentially create a more excellent elasticity in the field and provide more options to consumers with the farmers they choose to buy from. This takes away from much of the security these farmers are used to and leads to unrest among smaller and mid-sized farming companies that rely on these government prices when market prices drop.

This protest has been dominated by Punjabi farmers and has taken a turn to involve Modi’s politics. Punjabi farmers were the most affected by the Green Revolution and so own precious land. Under the free market laws that Modi looks to implement, these farmers would lose the middlemen needed to manufacture and produce their goods.

After these three laws were enacted, the Punjab Vidhan Saba, or legislative assembly, rejected the laws and removed themselves from the central laws. This sparked the growth in other states, such as Haryana, asking for similar treatment. The Chief Minister of Haryana, Dushyant Chautala, sided with the BJP, Modi’s party, and agreed with the laws, resulting in uproar in Haryana. Punjab’s main opposition party, Shiromani Akali Dal, led by Sukhiber Singh, has publicly voiced its support for the farmers and against the laws Modi enacted, creating a debate in the political field as well (Bhatia, 2021).

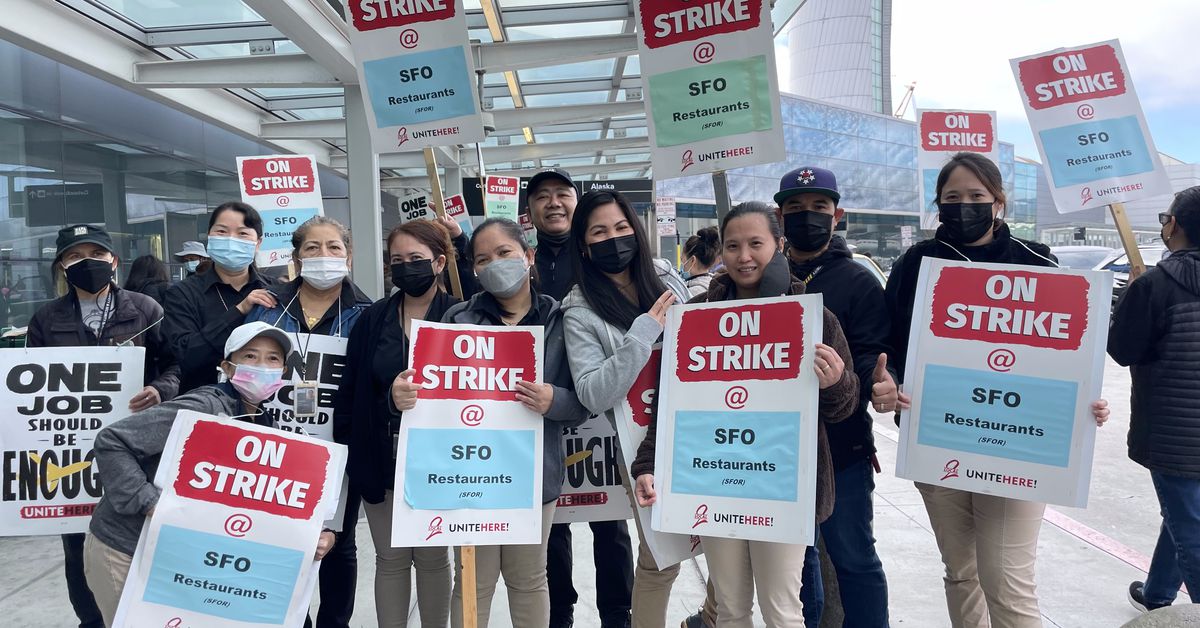

The protests have become increasingly violent, with officers shooting into the crowd, Twitter being banned, and many Hollywood and Bollywood celebrities speaking out over the issue. With more videos rising on violence towards protestors, the government has struggled to maintain peace and resolve the issue (Mashal et al., 2021). However, as the protests progress, amendments must be made to consider the farmers who would struggle with monopolization that would result from a free market and work alongside the people to prevent the affair from reaching more violent extents.

Sources:

Bhatia, Varinder. “Explained: Who are the Punjab, Haryana farmers protesting at Delhi’s borders?” indianexpress.com, 30 January 2021, <https://indianexpress.com/article/explained/punjab-haryana-farmer-protests-explained-delhi-chalo-farm-laws-2020/> Accessed 8 March 2021.

Frayer, Lauren. “India’s Farmer Protests: Why Are They So Angry?” npr.com, NPR, 2 March 2021, <https://www.npr.org/sections/goatsandsoda/2021/03/02/971293844/indias-farmer-protests-why-are-they-so-angry> Accessed 8 March 2021.

Mashal, Mujib, et al. “Why Are Farmers Protesting In India?” nytimes.com, NY Times, 27 January 2021, <https://www.nytimes.com/2021/01/27/world/asia/india-farmer-protest.html> Accessed 8 March 2021.

![Teacher [Milk] Tea: Part 2](https://bisvquill.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/Screen-Shot-2024-03-19-at-9.28.48-PM.png)