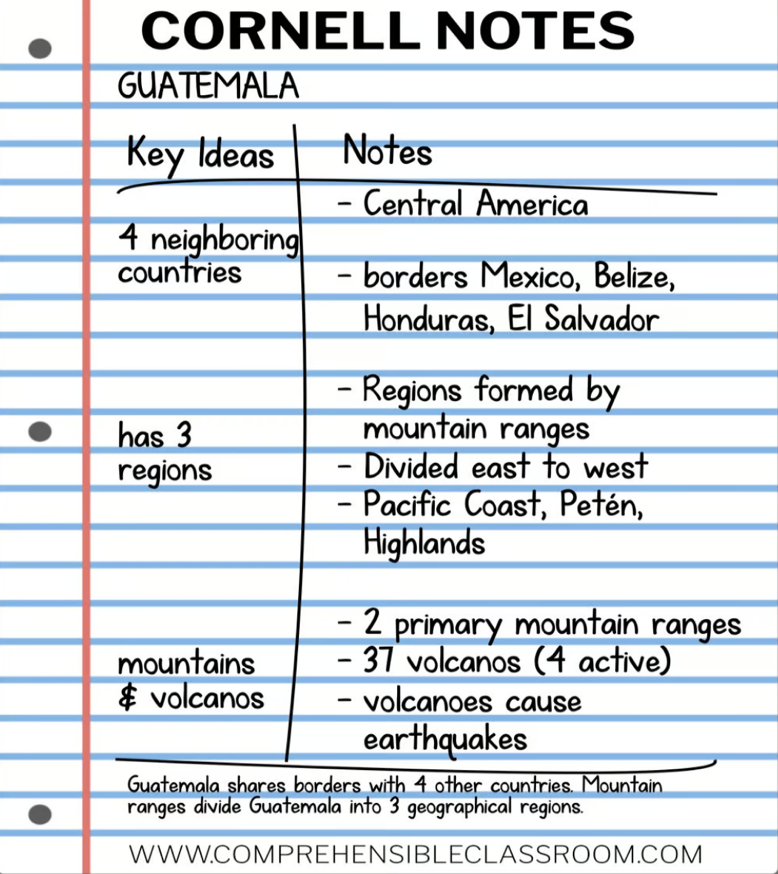

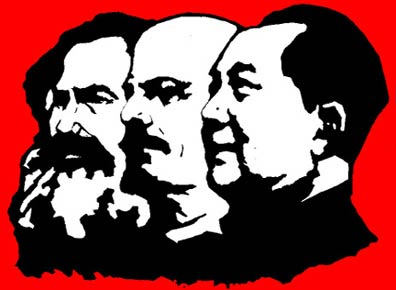

Wilhelm Steinitz (world champion 1886-1894)

After Morphy’s withdrawal from the chess world, the Romantic era progressed in full force. Players allowed their pieces to dance gracefully across the board, and it was believed that a brilliant attack would always trump a rigid, static defense. The rise of the Austrian player Wilhelm Steinitz shattered this worldview.

Wilhelm Steinitz was a player from Austria-Hungary (yes, we’re still in the 19th century…chess is old). Yet he was not an exciting player like his peers. He was not a brilliant tactician like Anderssen or a magical player like Morphy. Steinitz was a boring player, and that’s how Steinitz won.

Steinitz was the world’s first positional player. That meant he was more focused on the strength of his position as a whole rather than flashy tactics and sacrifices. Players who faced him were often frustrated by his unwaveringly firm style. Often, when his opponents would make seemingly clever sacrifices, Steinitz would remain calm, defend his king, and soon enough his opponent’s temporary advantage would collapse into an insurmountable deficit. This kind of play single-handedly ended the Romantic Era of chess.

By 1886, Wilhelm Steinitz was one of the strongest players in the world, but being far from the undisputed greatest as Morphy was, there was no way to confirm that title for sure. Thus, the first World Chess Championship was organized in 1886, where Steinitz would play another powerhouse of the era, Johannes Zukertort. The championship match lasted 20 games, of which Steinitz would dominate, winning 10 games to his opponent’s measly 5. The remaining 5 games ended in draws. Steinitz became the first World Chess Champion. Although this title was not as prestigious as it is today, it created a crown that generations of top players would vie for.

Steinitz was able to defend his title for a little less than a decade, winning three more matches after his initial victory. But in 1894, he was defeated by the rising master Emanuel Lasker. Though Steinitz accepted the defeat gracefully, other masters were not so open-minded to this… unorthodox player.

Emanuel Lasker (world champion 1894-1921)

Lasker did not play by the traditional rules of chess, and this led many to look down on him. Fellow grandmaster Siegbert Tarrasch declared that Steinitz lost the championship solely due to his advanced age, and that he himself could easily defeat a nobody like Lasker.

1908 World Chess Championship: Lasker defeats Tarrasch 10.5-5.5 points…

Lasker’s chess was considered “hypermodern,” meaning few could understand his moves. He also did this annoying thing where he would often play a move that was slightly worse than the best move, just to confuse his opponents and induce them to make a mistake.

Just imagine it: an entire generation of chess players made moves that looked right, and none of Lasker’s moves looked right! But they often were right, and his confounded opponents would frequently find themselves hopelessly lost.

Lasker was a believer in the Steinitz method: solid play was the way to win. But that didn’t mean he couldn’t unleash a tactical firestorm against his opponents. For evidence, please examine the following position.

Emanuel Lasker vs. Johann Hermann Bauer

In this position, black temporarily up a knight, but Bauer expects Lasker to recapture the knight on h5 with the Queen. So, he must have been quite shocked when Lasker lashed out with Bxh7+! sacrificing the bishop for a mere pawn! Bauer responded by recapturing with the king, Kxh7, and Lasker responded with Qxh5+, forcing the black king to retreat with Kg8.

Bauer was safe behind his pawn fortress, or so he thought. Bxg7! Lasker threw in a second dagger, exchanging another bishop for a defending pawn! Bauer was forced to play Kxg7 to avoid getting checkmated by the move Qh8. Lasker, now having opened up Bauer’s kingside, played Qg4+, forcing Bauer’s king to h7 (any other move would have resulted in checkmate). Then, to seal the deal, Lasker silently smothered his opponent with Rf3.

In this position, despite being up two bishops for two pawns, black has no defense against Rh3 checkmate except to sacrifice his Queen. The game lasted another 19 moves, but it was a losing battle for Bauer until his resignation.

The Other Greats of the Early 20th Century

In 1914, Tsar Nicholas II of Russia held the Moscow International Chess Tournament, the largest event of the year. The strongest masters in the world attended, and after many difficult and exhausting rounds, 5 finalists remained: Emanuel Lasker, José Raúl Capablanca, Alexander Alekhine, Siegbert Tarrasch, and Frank Marshall. Each of these men was given the title of grandmaster, beginning a tradition that lasts to this day. Of these five newly minted grandmasters, one was the sitting world champion, and two others would eventually gain that title. Of the remaining two, one, Tarrasch, was kind of a jackass, so I won’t feature any of his games. But the other, American master Frank Marshall, deserves his own spotlight.

The Gold Coin Game

Stefan Levitsky vs. Frank Marshall (1921)

Marshall is playing this position from the black side, so try to imagine this board flipped. Here, Marshall is up an entire knight, but Levitsky has counterattacking chances. In this position, if Marshall could trade the queens, the game would be over, and he would win. But what would be the most flashy way of winning in this scenario?

Qg3!!

WHAT?! Moving a queen onto a square where it can be captured by three different pieces? However, as it turns out, this position is completely lost for white. How is that possible? Let’s take a look.

The most crisp ending to this game would occur if white played hxg3, because black would respond Ne2#. The rook on h3 (which, btw, is hanging), covers both of the white king’s escape squares.

fxg3 would prolong the suffering only minimally. After Ne2+, forcing white’s king to h1, black would seal the deal with Rxf1#.

The only logical continuation here would be, counterintuitively, Qxg3, but this would be met with Nd2+ followed by the queen’s recapture. At that point, white would be down a full minor piece with no compensation. So, rather than suffering further, Levitsky resigned.

The story goes that bystanders were so impressed by this game’s sparkling ending that they covered the board with gold coins! Chess was a rich man’s game back in the day.

1921 also happened to be the same year in which Lasker, now old and out of practice, would lose his title as the Chess Champion of the World.

TO BE CONTINUED…

![Teacher [Milk] Tea: Part 2](https://bisvquill.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/Screen-Shot-2024-03-19-at-9.28.48-PM.png)