On September 14th, 2023, as I was entering BISV, I realized the American flag was flying at half-mast. But there was no air of gloom. The sun was as vibrant as ever, the students’ chatting unbroken. Not even the history teachers mentioned what happened 22 years ago, when the skyline of New York City was suddenly choked with black smoke and the United States declared war on terrorism.

The day’s events got me thinking: if nobody remembered how terrorists struck a painful blow to our democracy on September 11th, 2001, how would anyone remember how America crippled Chilean democracy on the same month and day? The story of September 11th, 1973, has long been buried in the paragraphs of history. 50 years later, I think it’s a good time to dig it back up.

The year was 1973, less than a year before the Nixon administration’s end. The Cold War still dominated global news. America had recently pulled their troops out of Vietnam, allowing the Communists to seize control of the entire country. The US had failed to stop Marxist Fidel Castro from seizing control of Cuba and building a cult of personality around himself, and the USSR, the big brother of Communism, showed no signs of decline. Despite the US’ reconciliation with China earlier that year, the US still viewed leftist governments of any kind as a major threat.

Now, allow me to introduce Salvador Allende. Elected President of Chile in 1970, he was an unabashed Marxist who the US tried to block through electoral interference. But when that subtle plan failed, the US resorted to a more “indelicate” one.

After United States-backed coups had installed military governments in Brazil, Argentina, Bolivia, and Peru, they turned their attention toward Chile. By this point, most Chileans were already upset that the nation’s economy had failed to improve since Allende took office. US sanctions that resulted in a national economic downturn were blamed on President Allende. On August 22nd, 1973, the Chilean Congress accused Allende of amassing dictatorial powers. The pieces for a coup were in place.

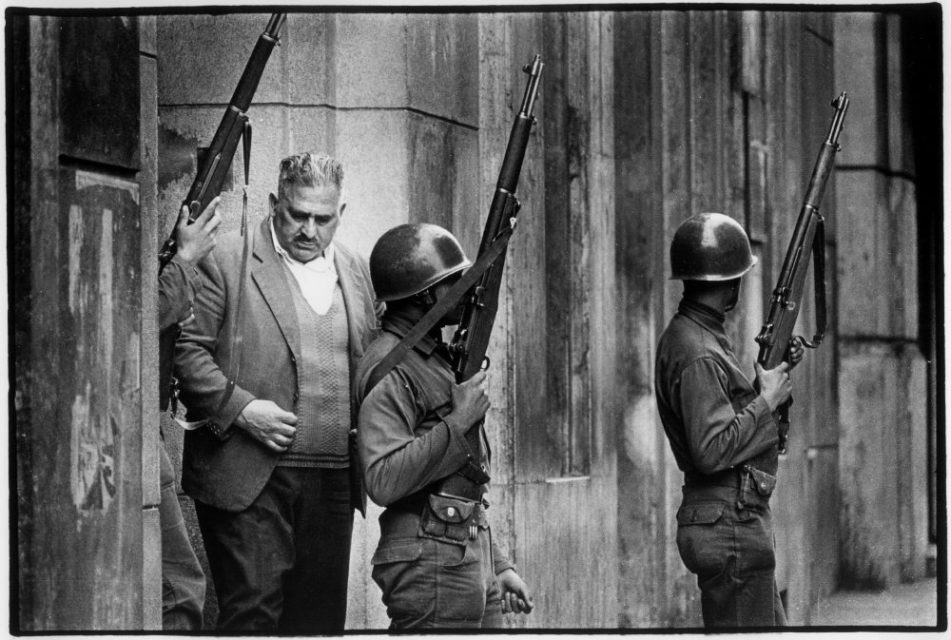

Early on September 11th, the Chilean Navy began the coup by seizing coastal regions and shutting down television networks. Allende, believing this to be no serious threat, led his bodyguards, the “Grupo de Amigos Personales” (GAP), back to the Presidential La Moneda Palace. There, he learned that the Army and Air Force had also joined the coup, and were shutting down all communications in the capital. By 8:30 AM, they had declared Allende overthrown and a new government established. Only then did Allende realize how dire the situation truly was. He had naively believed the head of the Armed Forces, Augusto Pinochet, was still on his side. Only now did he realize the extent of the army’s betrayal.

By 9:00 AM, the police force of the city, responsible for La Moneda’s protection, had left the building. Despite this mass betrayal, Allende still refused to surrender. “I will not resign!” he declared over the sole remaining radio station as gunshots sounded in the distance. “These are my last words, and I am certain that my sacrifice will not be in vain.” The army did give Allende the chance to leave the country, but he declared that he would complete his duty to the country and to the presidency until none of his bodily strength remained. Meanwhile, the tank commanders had completely encircled the palace, and the Air Force bombarded it from above. Wave after wave of attacks were driven back by GAP, but it was clear that the palace would soon fall.

Image: Wikimedia

As smoke billowed into the clear blue sky and the president’s bodyguards dwindled, Allende decided that the bloodshed needed to end. He ordered the palace’s defenders to stand down and personally thanked each and every one of them for their faithful service. Then, at 1:50 PM, Allende, using an AK-47 gifted to him by Fidel Castro, riddled his body with the bullets of martyrdom.

Allende could hardly be considered a successful president. His administration was marred with protests, scandals, and overshadowed by a failing economy. But these failures were nothing compared to the actions of his successor, General Augusto Pinochet, who, after coming to power, immediately shut down the Congress and other democratic institutions and styled himself as a military dictator. One of his first acts was to authorize the “Caravan of Death” brigade to execute those held in army captivity across the nation. Those prisoners, along with members of Allende’s captured cabinet, were executed. With US backing, Pinochet would go on to execute between 1,200 and 3,200 “leftists and socialists.” Tens of thousands more were brutally tortured. Pinochet even went so far as to assassinate Orlando Letelier, Allende’s defense minister, in the middle of Washington DC. But none of these actions discouraged US support.

Today, there is still much debate in Chile whether the coup was justified. Nearly a third of Chileans say it rescued the nation from Marxism, and the leader of Chile’s opposition party, Jose Antonio Kast, refuses to condemn the coup and has boasted that “if [Pinochet] were alive, he would vote for me.” Nonetheless, the general consensus, domestically and internationally, is that Pinochet’s regime was one of the most brutal in 20th century South American history. Operation Condor, an anti-leftist campaign began by Pinochet, would see tens of thousands of mysterious kidnappings and deaths.

Earlier this year, the CIA admitted to having played an active role in facilitating Pinochet’s rise to power. The wider Operation Condor also enjoyed significant US backing. In 2006, nearly two decades after the restoration of civilian government in Chile, Augusto Pinochet died, never having been held accountable for his crimes.

If we asked most Americans today what the legacy of the Nixon Administration was, most would recall Watergate. Few Americans remember his actions abroad, whether it be the coup in Chile or the bombing of Cambodia. Yet it is those actions that have destroyed the lives of thousands, and continue to haunt America’s global image today.

![Teacher [Milk] Tea: Part 2](https://bisvquill.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/Screen-Shot-2024-03-19-at-9.28.48-PM.png)

![Teacher [Milk] Tea: Part 1](https://bisvquill.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/milk-tea.png)